Time and Space | The ShelterPhysics Blog

Posts Filtered by Tag - Forces |

Show Recent Posts

August 8, 2025

Turn Posture on a Skateboard

Turn Posture on a Skateboard

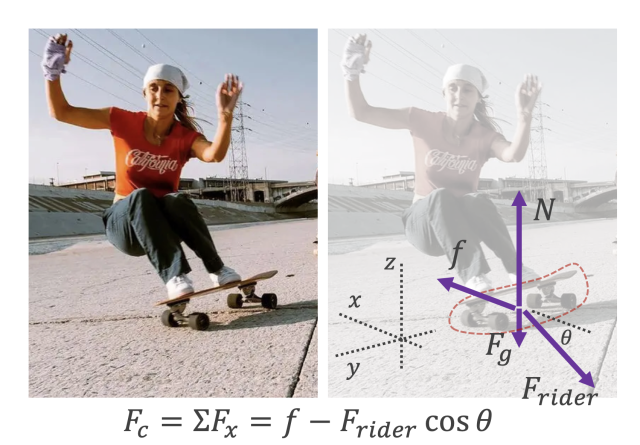

One of Mitchie Brusco's excellent SkateIQ videos caught my attention, especially when he discussed body position while turning.

Mitchie demonstrates the correct posture for an aggressive toe-side carve (turn) with the help of a cinderblock wall.

Starting at 10:13 in the video, Mitchie requires the use of a cinderblock wall to illustrate proper body position while turning. Those who read my previous article on body position while turning on a snowboard will recognize that the wall is needed because Mitchie's center of mass is outside the skateboard trucks while turning. Unless he's actually turning on his board, he can't maintain the correct posture without falling. In this respect, snowboarding and skateboarding share the same physics.

The difference between snowboarding and skateboarding, though, is that the rider is attached to the snowboard. (What's the difference between a snowboard and a vacuum cleaner? How the dirtbag is attached.) We can much more reliably model the snowboard and its rider as a single object. For the skateboard, we need to worry about the board "following us into the turn," to use Mitchie's language. If it doesn't, we will fall.

So why does the skateboard "follow us into the turn?" Let's model the skateboard as an object. It experiences a force from the rider down and to the outside of the turn. Normal force from the ground points up, gravity (on the board itself) pulls down, and friction points inward, since the board is being pushed outward by the rider. It's not obvious, though, that the friction inward would be greater than the rider's outward push, a condition which is necessary to create a centripetal force on the skateboard.

Original Photo: wake20

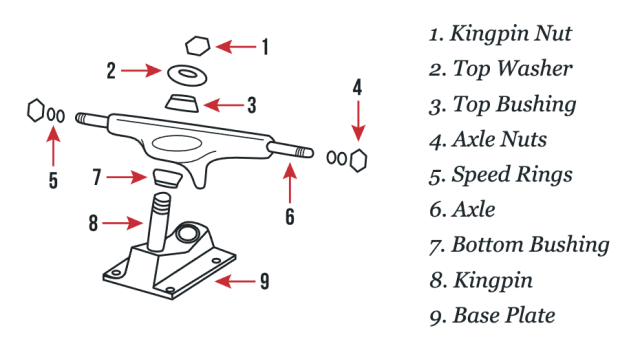

It turns out skateboards need a mechanism to generate centripetal force, in the form of friction. That mechanism is in the trucks, the assemblies that connect the wheels to the skateboard. The trucks are designed to respond to a skateboard leaning to one side by turning the wheels into the lean, angling them not unlike turned front wheels on a car. And like wheels on a car, the angle creates friction which forces the skateboard inward.

Parts of skateboard trucks. Source: SkateDeluxe

The combination of the angle of the kingpin toward the front edge of the board (front truck) or toward the back edge of the board (rear truck), combined with the shape of the bushings, pivots the axles to create additional friction directed inward during a turn.

There is so much more good physics in Mitchie's video. As he discusses how to fall without hurting yourself:

There are only a few areas that we have to protect. We do that by spreading the impacts out over a bigger surface area.

Pressure (force ÷ area) is what determines whether a person will injured during a fall. Many safety devices (helmets, pads, air bags in cars, and so on) work by spreading the force of collision over a bigger area.

Later in the video, when Mitchie is discussing how to do Ollies (jumps where the board follows you into the air), he says this:

What I want you to get the hang of is how you can hook your front foot on the nose and pick the tail up with a little bit of leverage so that your board rotates into the air like a pendulum.

In an Ollie, the tail of the board bounces off the ground and the board recoils into the air. The front foot is used to create a pivot point. The board rotates back into the horizontal position as its translational kinetic energy is converted to rotational kinetic energy and eventually to gravitational potential energy. We are not so much picking up the tail of the board as creating a fixed point which holds the nose of the board in place while allowing the inertia of the board to bring the tail up level with the nose.

Watch the full video and see how many connections you can make.

May 5, 2025

Body Position While Skidding and Carving on a Snowboard

Body Position While Skidding and Carving on a Snowboard

My interest in snowboarding prompted another online conversation, this time about skidding and carving and forces and torques.

Malcolm Moore skidding on his heel edge (left). An AI-generated image with decent snowboarding posture (right).

I had posted with tips on how to successfully skid down the hill on the heel edge, as shown in the photos. It was a physics-based explanation focusing on the importance of one's center of mass being vertically over the engaged edge of the snowboard.

A commenter said this:

Your center of mass NEEDS to be outside the heel edge to counteract the force of sliding down the hill forwards, that's why it's so tricky, because you've got to lean a little further back than you feel comfortable with. Part of the battle is getting used to knowing that you need to shift your center of mass outside of where your body knows it can balance, coupled with the slipping feeling.

To which I replied:

There is no "force of sliding down the hill." A force is a push or a pull from another object. In this case, there are three significant forces on the rider/board object: gravity, friction with the snow, and the normal force (the push of the snow 90 deg to its surface). Skidding at constant velocity, these forces must be balanced (the vector sum must be zero). Torques about the pivot point (the heel edge of the snowboard) must also sum to zero. When they don't, you fall. You can see from the diagram that friction and the normal force act through the pivot point, the edge of the snowboard. Hence, no torque from them. That's why weight must be stacked over the edge. If it's not, they'll be a torque from the rider's weight and they will fall.

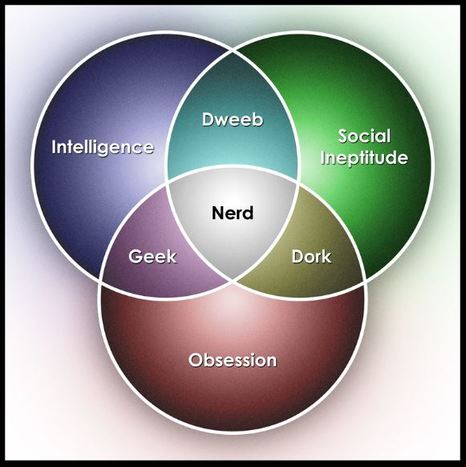

Admittedly, I did not provide a comprehensive answer likely to convince anyone unfamiliar with physics. Instead, I attempted to thread the needle between a comprehensive response and a concise response. In particular, I did not define torque, nor explain why positioning one's center of mass over the heel edge would eliminate it. So maybe this experiment in outreach was doomed to fail. Someone closed an extended, acrimonious exchange by calling me a "dork." ☺️ (For the record, I identify as "geek," though "nerd," sadly, is often more descriptive of my state of being.)

After some reflection, I began to appreciate that a big part of the confusion was a failure to differentiate between skidding down a hill on the heel edge and making a turn on the heel edge. While making a turn, it is absolutely normal and desirable to position one's center of mass to the inside of the turn. Much advice about body position in turns relates to getting the correct angle between the contact point of the engaged edge and center of mass. What might that angle be?

Let's simplify things a bit by imagining a turn along a circular arc, at constant speed, on level ground, and with a negligible difference between the radius of the turn and the (slightly smaller) radius traversed by the center of mass. We apply rotational dynamics to this scenario. (Original photo: Snowboard Addiction)

Let's simplify things a bit by imagining a turn along a circular arc, at constant speed, on level ground, and with a negligible difference between the radius of the turn and the (slightly smaller) radius traversed by the center of mass. We apply rotational dynamics to this scenario. (Original photo: Snowboard Addiction)

Looking from the top, we examine the radius of the turn R and the projection of angular momentum onto the horizontal plane.

Rotating the orange triangle back into the side view, we see that dL points out of the page, the same direction as torque. Writing Newton's second law in angular form:

We recognize this as the same formula derived from force considerations for a banked turn without friction. Indeed, the two scenarios are analogous, as both objects lean into the turn, and both exist in a non-inertial reference frame as a result of their circular motion about a stationary point with radius R.

In a typical scenario, with a rider cruising at 12 m/s (27 mph) and turning with a radius of 9 m (30 ft), the necessary angle would be about 59 degrees.

Googling around, it's possible to find many different workable postures for effective carving: some folks with deep bends at the knees, others standing more erect. Are these differences related to the fact that lean angle appears in the formula, but not distance from the engaged edge to the center of mass (r)?

Every snowboarder has had the experience of leaning in too far on a turn. If the rider retains grip, they don't simply fall over. Instead, the board tracks with a smaller and smaller radius of turn until there is a kind of spin out. The larger the angle of lean θ, the smaller must be the radius of the turn. Unless of course, the rider balances out some of the torque by putting their inside hand or forearm on the snow.

September 30, 2024

Jet on a Conveyor Belt

Jet on a Conveyor Belt

The airplane on the conveyor problem has been around for a while. It keeps popping up in my social media, though. I decided to approach it from a slightly different place, emphasizing the actual performance of the airplane.

The question is poorly-worded. (Physics questions on the Internet are often poorly-worded, to create attention as commenters argue with each other.) No frame of reference is provided for the "speed of the wheels." Nor is the point on the wheel specified. Comic artist and uber-geek Randall Munroe (xkcd) has explored the possibilities. The only scenario which makes physical sense is where the wheel speed is measured from its center of mass relative to Earth, and the conveyor speed is measured in the same way.

Spoiler

The airplane can take off. As it does, the wheels will be spinning at twice their normal rate, which could create problems if engineering specifications are exceeded.

Knowns

A force diagram for the airplane on the runway is shown below.

It is possible that both drag and lift will be greater than zero at rest, if the airplane is pointed into the wind (as is normal for takeoff). Friction between the wheels and the runway arises from rolling friction and the need to increase the rotational speed of the wheels.

Internet searches yield the following typical data for a 747.

airplane weight = 800 kilopounds = 3.56 x 106 N

airplane mass = 3.63 x 105 kg

airplane thrust = 60 kilopounds per engine(4 engines) = 240 kilopounds = 1.07 x 106 N

number of wheels = 18

wheel radius = 0.62 m

wheel mass = 184 kg

wheel moment of inertia = 46 kg•m2

wheel effective coefficient of rolling friction = 0.02 (on concrete)

Using this information, we can explore the dynamics of takeoff.

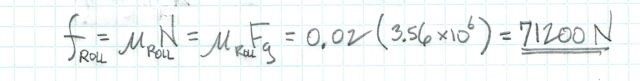

Calculations

The average acceleration of the airplane during takeoff can be estimated from this video as 1.8 m/s2, from zero to 90 m/s in 50 seconds. Nominally, the maximum acceleration would be 2.95 m/s2 (=thrust/mass, excluding resistive forces).

The frictional force required to create angular acceleration in the wheels is quite small in relation to the thrust of the engines. Even if this number is doubled by the motion of the conveyor, it is still less than one percent of the engine thrust.

Due to the significant weight of the airplane, the rolling friction of the wheels creates a much greater resistive force, perhaps 7% of the engine thrust.

Rolling friction is quite variable depending upon runway surface and total airplane weight. It will be diminished by lift from the wings, which causes normal force to be less than airplane weight.

The original question asks, can the airplane take off? We conclude that the airplane has the net force needed to accelerate to takeoff speed in spite of the conveyor, so long as rolling friction on the conveyor is not excessive. If somehow the conveyor exerted greater resistive forces on the airplane—if its design were more exotic than what we are led to believe—the airplane could of course be prevented from taking off.

SEARCH NEWS ITEMS

SEARCH ARTICLES

POSTS BY TYPE

POSTS BY TAG

POSTS BY MONTH